Park History

About the Park

Broad Ripple Park, located at 1500 Broad Ripple Ave, is a 62-acre park currently features a family center, a seasonal swimming pool, playground, picnic shelters, tennis courts, baseball diamond, multi-use athletic fields, fitness trail, boat ramp, and dog park.

Find park hours and information.

Early Development

What is known today as Broad Ripple Park began simply as a farm, frequently visited by picnickers. The original 60-acre farm, then north of Indianapolis, was established by Jonas Huffman in 1822. In the 1860s, during the ownership by his son, James Huffman, and business partner, Charles Dawson, the riverside parcel became a favorite picnic spot for people from the surrounding area. The 1890s brought electrified streetcars to Indianapolis and Broad Ripple, making transportation between the two easier than ever. This newfound access to the countryside of Broad Ripple attracted Indianapolis residents to utilize it as a summer retreat. One man not only helped create this opportunity, but also capitalized on it by creating an amusement park on the former Huffman-Dawson farm parcel.

White City Amusement Park

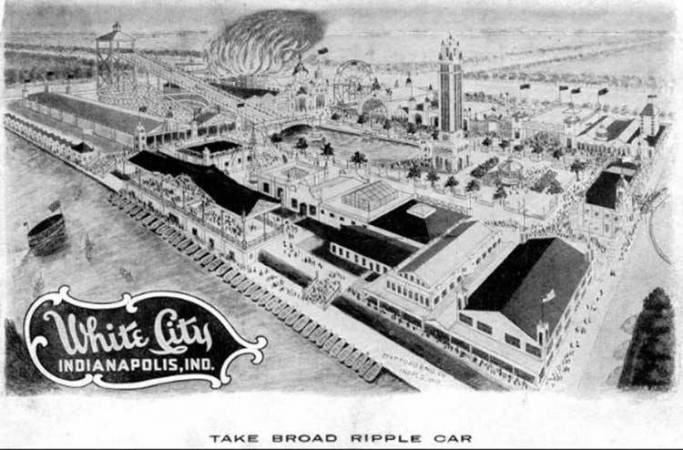

Dr. Robert C. Light greatly aided in the development of Broad Ripple in the late 1800s and early 1900s through his entrepreneurial endeavors. Dr. Light, along with William Bosson, created the Broad Ripple Transit Company in 1894. “Its line had the distinction of being the first electric interurban railway to be constructed and placed in operation in the United States” (History of Greater Indianapolis). He also formed the Broad Ripple Gas Company in 1896. In the fall of 1905, Light, along with Raymond P. Van Camp, Milton S. Huey, John W. Bowles and Leon O. Bailey created the White City of Indianapolis company. White City of Indianapolis was created with the singular goal of creating an amusement park at the end of the Broad Ripple Transit Company’s College Line, benefiting both companies, both in which Dr. Light had stake.

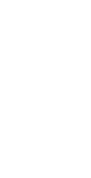

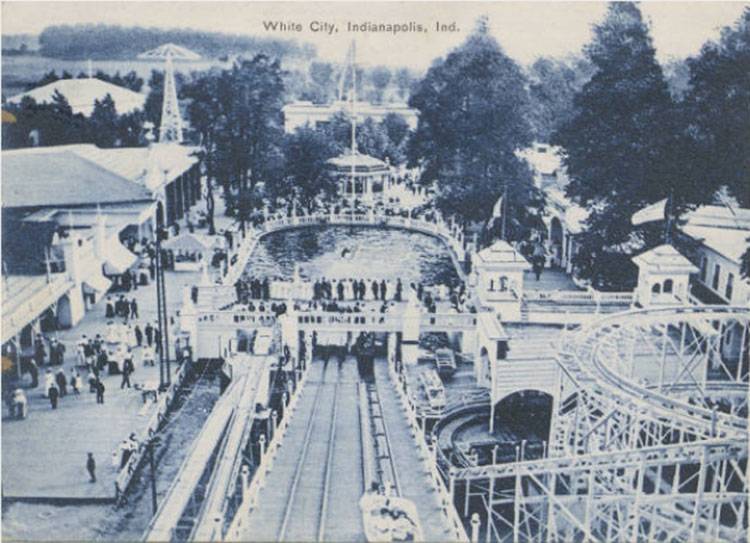

Named “White City Amusement Park” in homage to the Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition, the park formally opened on May 26, 1906. It was the last to open of three amusement parks in the Indianapolis area at the time. Inspired by the success of Coney Island in New York (and often duplicating attractions from it) the three local amusement parks, Riverside, Wonderland and White City, competed for the business of the community and the larger surrounding area between 1906-1908. Regular inter-urban and streetcar schedules on College Avenue between Broad Ripple and Indianapolis meant visitors could reliably get from the north side of city to the White City Amusement Park in about five minutes.

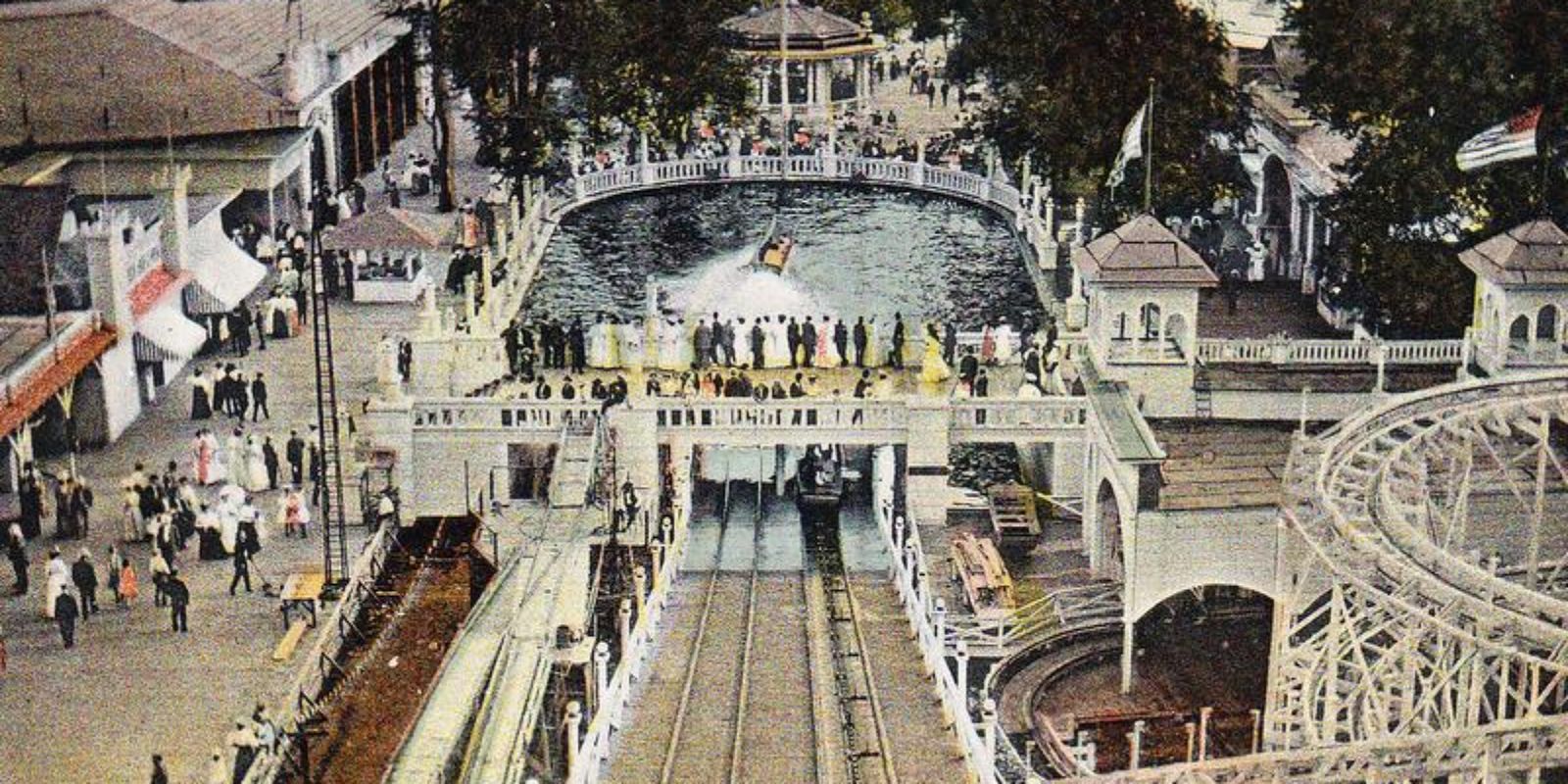

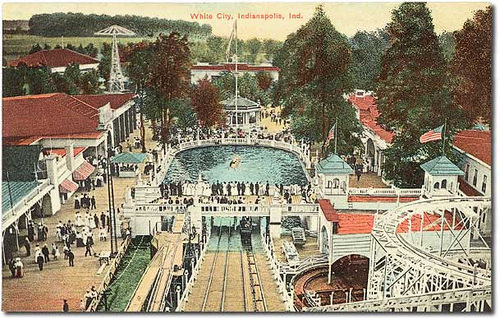

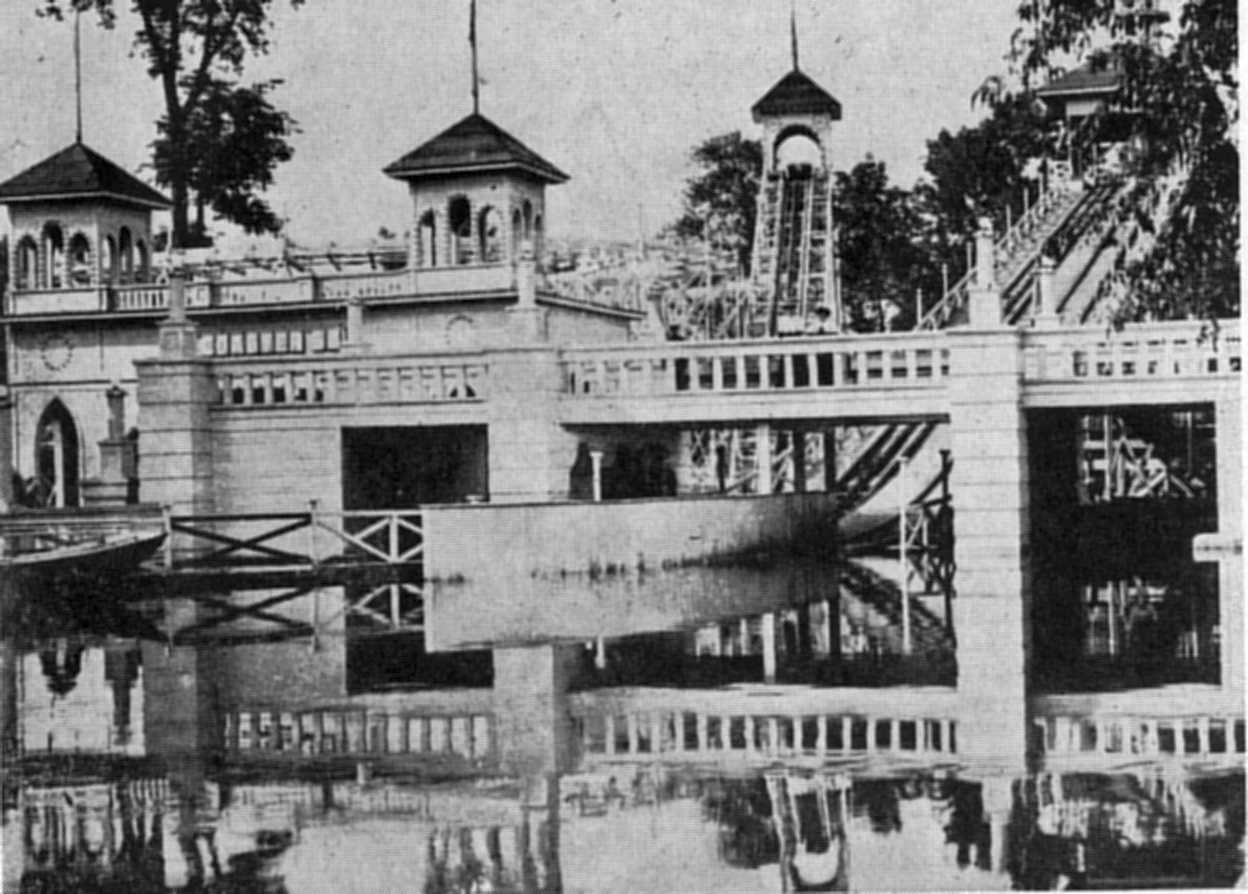

Though all three parks duplicated not only Coney Island’s attractions and shows, but also each other’s, there were a few things that made White City stand out from the other two. One, the first park manager, W.C. Tabb had a boardwalk installed (meant to be reminiscent of Coney Island’s). The boardwalk took visitors on a walk “around its sea of tall trees” (Indianapolis Amusement Parks 1903-1911). Two, though all the parks had a “Shoot-the-Chutes” (think Disney’s Splash Mountain), White City had a bridge crossing over it, allowing onlookers to watch from above as the boats splashed into the artificial lake. Three, again inspired by Coney Island, the White City had on display “Baby Incubators” – incubators meant to warm premature infants to help aid in their survival. German physician, Martin Couney, first encountered a preemie baby exhibit in 1896 at the Berlin Exposition – and recreated the successful attraction in the U.S. at Coney Island in the early 1900s. The predecessor to the baby incubators we know today were tested and popularized by amusement parks, like White City, before being utilized in hospitals!

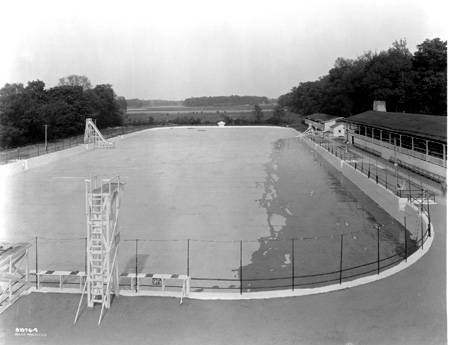

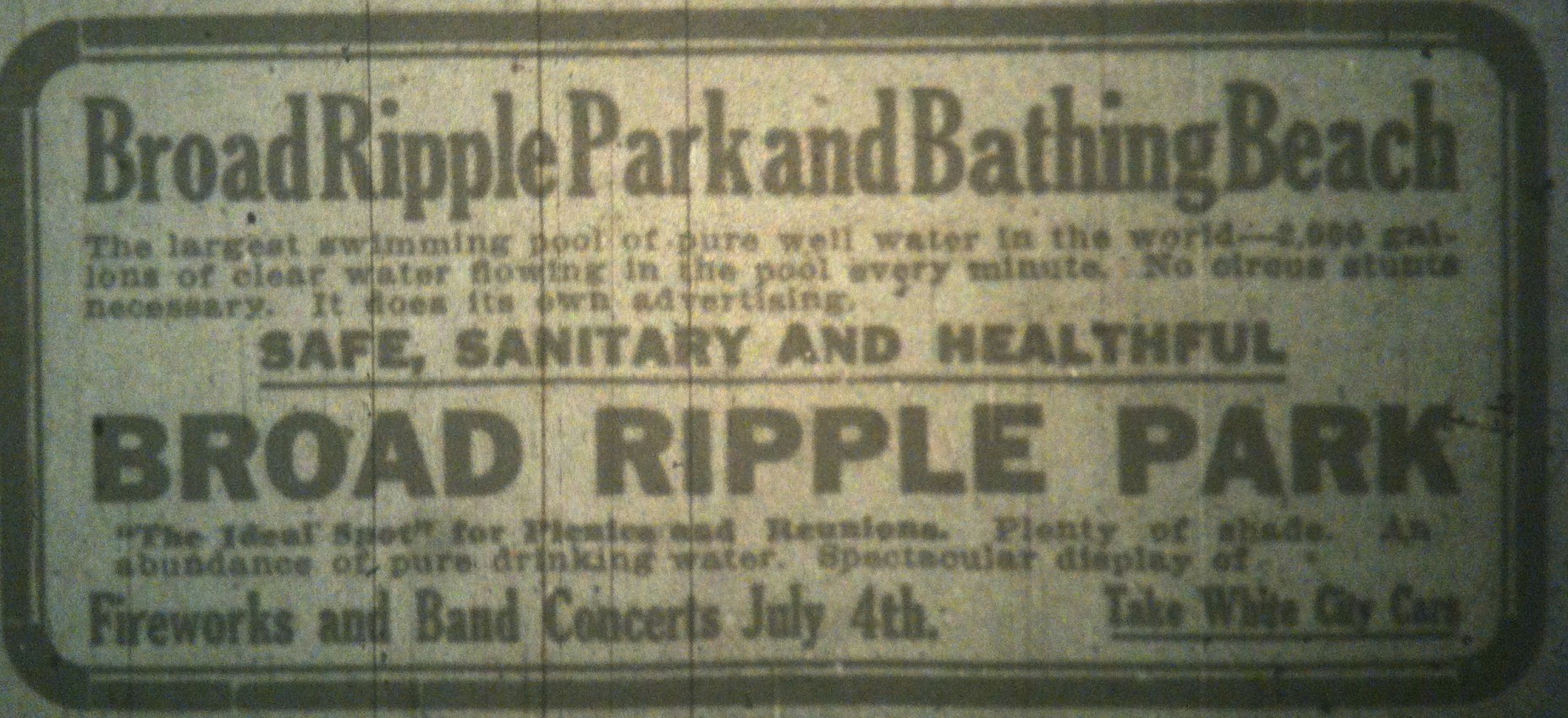

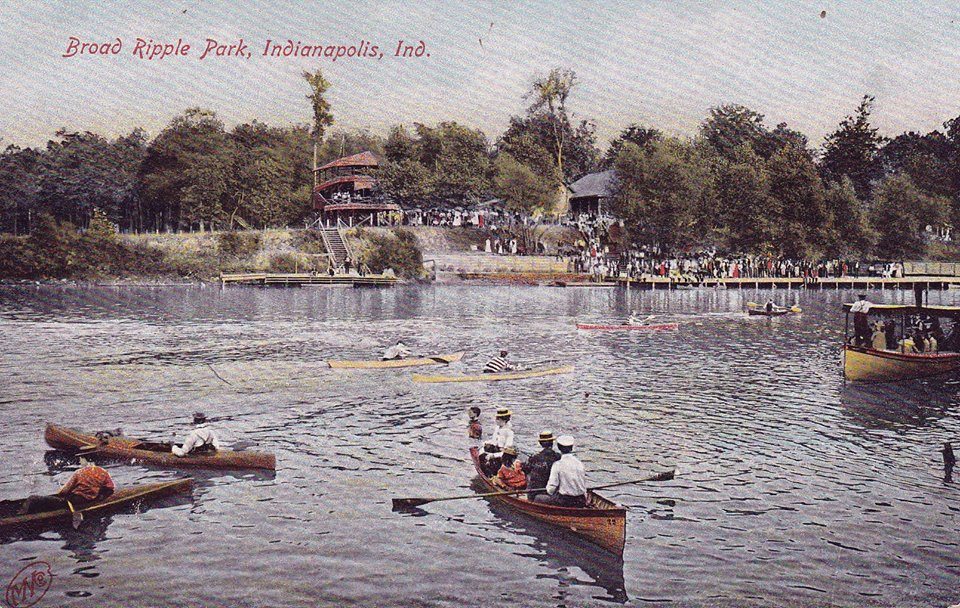

White City, like Riverside, also emphasized their proximity to the White River. Visitors were enticed by access to water leisure activities such as boating – including on river steamers, canoeing, and swimming. Banking on that appeal, White City invested heavily in building up those aspects, first with a “concrete lined bathing beach along the river” and then in 1907, with a plan for a four-acre swimming pool area, which the Park was claiming as “the largest affair of the kind in the country” (Broad Ripple). The pool was to open on June 27, 1908. However, on the 26th, nearly the entire White City Amusement Park burned to the ground. The catastrophic (though not fatal) fire took less than 10 minutes to engulf the park. Only the pool and its structures remained unscathed. Estimated damages were around $160,000 (nearly $4.5 million in today’s money), of which there was only $1000 worth insured.

The Pool

White City had been correct that the pool would become a major attraction, they just didn’t know it would become the only one for several years. Despite the loss of the rest of the park, the 250×500 feet pool still had its opening, just a couple weeks later on July 4, 1908. The pool continued to operate, but a replacement amusement park didn’t come to fruition until several years later, under new ownership – The Union Traction Company purchased the park in 1911. Under the Union Traction Company, the new renovated park boasted a new boathouse and 10,000 square foot dance hall in addition to the standard rides and attractions, and of course, the remaining pool.

The pool continued to be the chief attraction. In 1922, Broad Ripple Amusement Park hosted the National Swimming Event. The pool – and park, had its brush with fame when the it had the honor of hosting the Olympic tryouts in 1924. Johnny Weissmuller, who would go on to play Tarzan, won the qualifier for the 100m freestyle and also went on to win Gold at the Olympics in this category the same year. The pool again hosted the Olympic tryouts in 1952. This time, the city got to send one of its own, Broad Ripple High School graduate, Judy Roberts, to Helsinki as a member of the U.S. Olympic Swim Team.

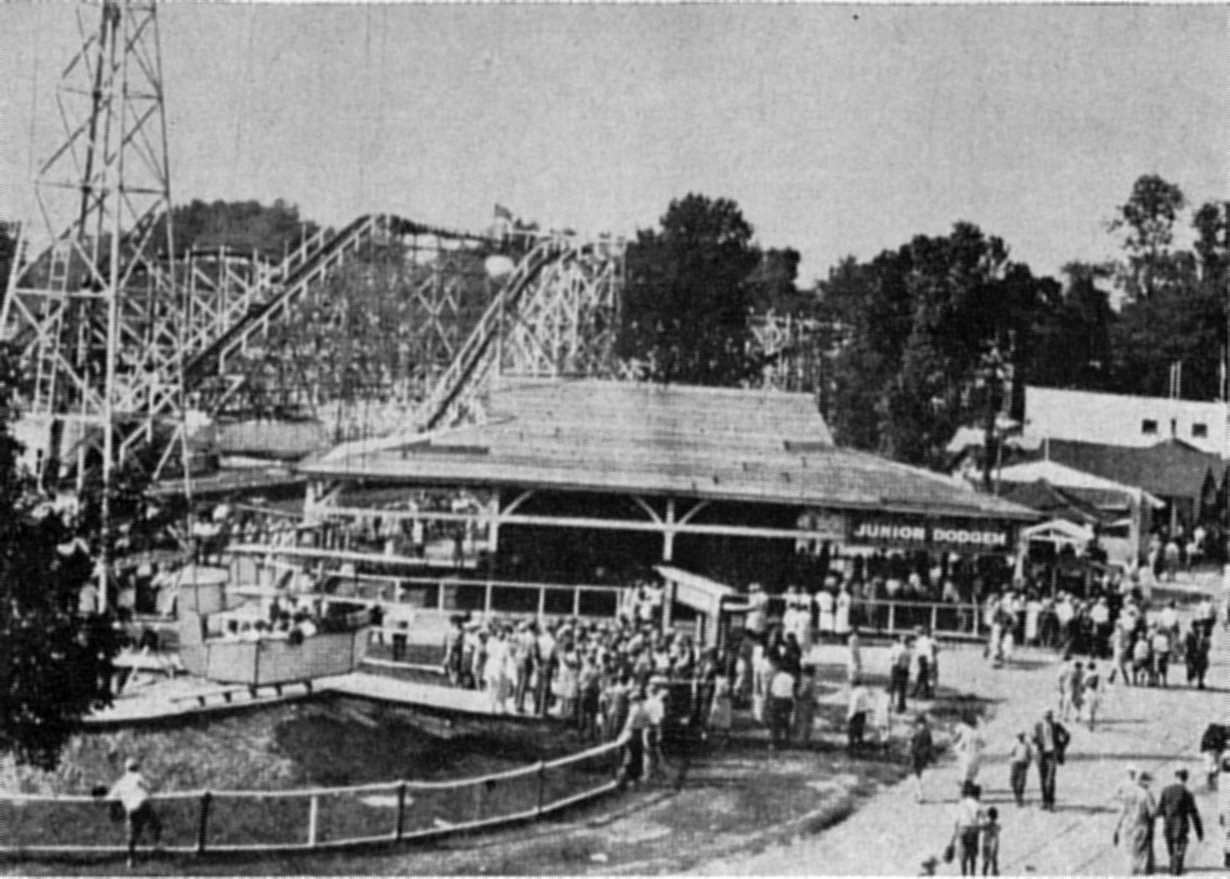

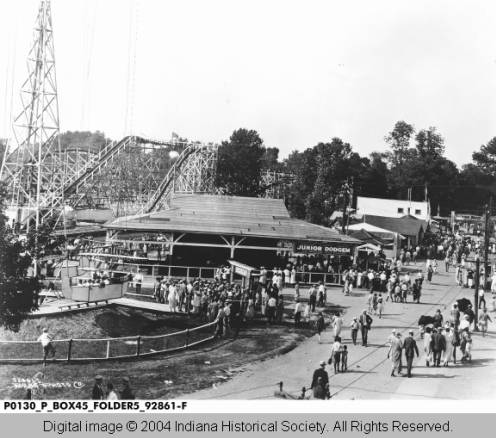

From Amusement Park to City Park

From farm to amusement park to city park, Broad Ripple Park has changed hands many times. Each new ownership brought additional enhancements to the Park. The Union Traction company sold the park in 1922 to the “Broad Ripple Amusement Company” (BRAC). It was then that the park became known as Broad Ripple Amusement Park. During the BRAC’s ownership, athletic fields, additional bath houses and a giant roller coaster were added. However, BRAC sold the park, only five years after purchasing it, to Oscar Baur, an executive of the Terre Haute Brewery. He was interested in modernization and removed many of the rides rebuilt after the 1908 fire. Baur also added the “Huffman’s Auto Speedway” and had the pool remodeled. The pool remodel included a well to fill it with fresh water rather than river water.

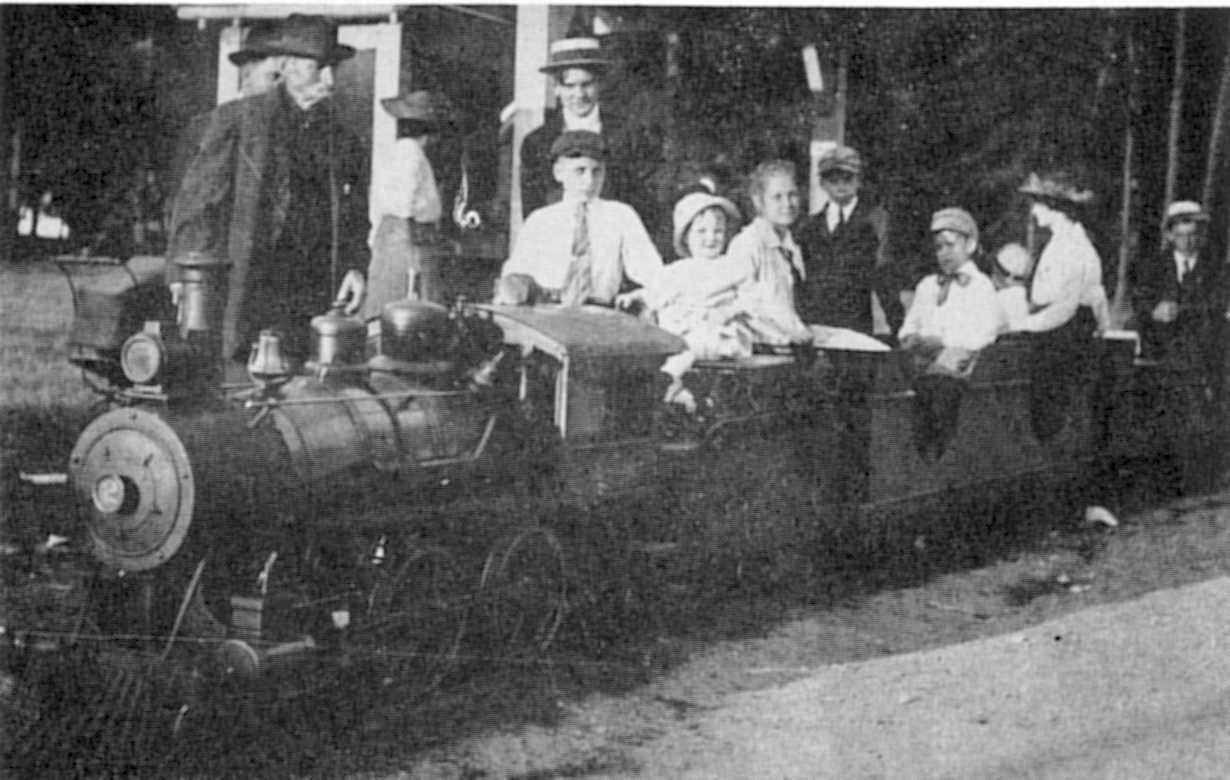

The City of Indianapolis officially purchased the park in 1945 and went to quick work dismantling and/or selling the remaining rides. However, a 1917’s Carousel, which had been placed in the park during the Union Traction Company’s ownership, has been loving restored (and updated) and currently resides in the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. In 1955, several years after the City took ownership, Broad Ripple Park had the steam locomotive, Nickel Plate Road 587, put on display within the park. It remained in the park until 1983 when it was removed to make way for the new Public Library. The locomotive was taken to be restored and then became a part of the Indiana Transportation Museum. It is currently under another restoration and is expected to return to operation in 2018 or 2019.

Today

Today, Broad Ripple Park is a 62-acre park on the northeast side of Indianapolis, bordering the White River. It offers a wide variety of programs and activities for all ages, and welcomes an estimated 150,000 visitors annually. The Family Center schedules scores of classes throughout the year in dance, safety, sports, fitness, arts, crafts, health, self-defense and other subjects for all age groups. Programs are generally fee-based, and registration is usually required.

In addition to the Family Center, Broad Ripple Park facilities include an outdoor swimming pool, tennis courts, baseball diamond, multi-use athletic fields, playground, picnic shelters and areas, a viewing platform over the White River, a bark park, a wooded preserve, a walking/jogging/running/bicycling and fitness path, and a boat ramp to the White River (www.broadripplepark.org).

Bibliography

“Broad Ripple Park Carousel.” Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broad_Ripple_Park_Carousel. Accessed 07 February 2018.

Broad Ripple Park, Indianapolis. Friends of Broad Ripple Park, 2018. www.broadripplepark.org/. Accessed 08 February 2018.

Dunn, Jacob Piatt. Greater Indianapolis, Vol. II. The Lewis Publishing Company, 1910.

Hibschweiler, Don. “Remembering Indy’s Amusement Parks: White City.” Wfyi Indianapolis. www.wfyi.org/news/articles/remembering-indys-amusement-parks-white-city. Accessed 07 February 2018.

“How a Coney Island Sideshow Advanced Medicine for Premature Babies.” PBS News Hour. 21 July 2015. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/coney-island-sideshow-advanced-medicine-premature-babies. Accessed 08 February 2018.

The Junior Historical Society and The Riparian Newspaper. “Park Attracts Tourists.” A History of Broad Ripple. Broad Ripple High School, 1968, Chapter 11. www.broadripplehistory.org/br_ch11.htm. Accessed 07 February 2018.

“Nickel Plate 587.” Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nickel_Plate_587. Accessed 07 February 2018.

The Polis Center. “Broad Ripple.” IUPUI. http://www.polis.iupui.edu/RUC/Neighborhoods/BroadRipple/BRNarrative.htm. Accessed 07 February 2018.

Vanderstel, David G. and Connie J. Zeigler. “Broad Ripple Park (White City Amusement Park).” The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, edited by David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, Indiana University Press, 1994, pp. 353-354.

Zeigler, Connie J. “Indianapolis Amusement Parks, 1903-1911: Landscapes on the Edge.” MA thesis, Indiana University, 2007. scholarworks.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/1805/1595/thesismerged.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 07 February 2018.